One of my most popular posts is about how I use the YouTube API to add a music playlist to my homepage. It's totally unnecessary and impractical—but it's a lot of fun.

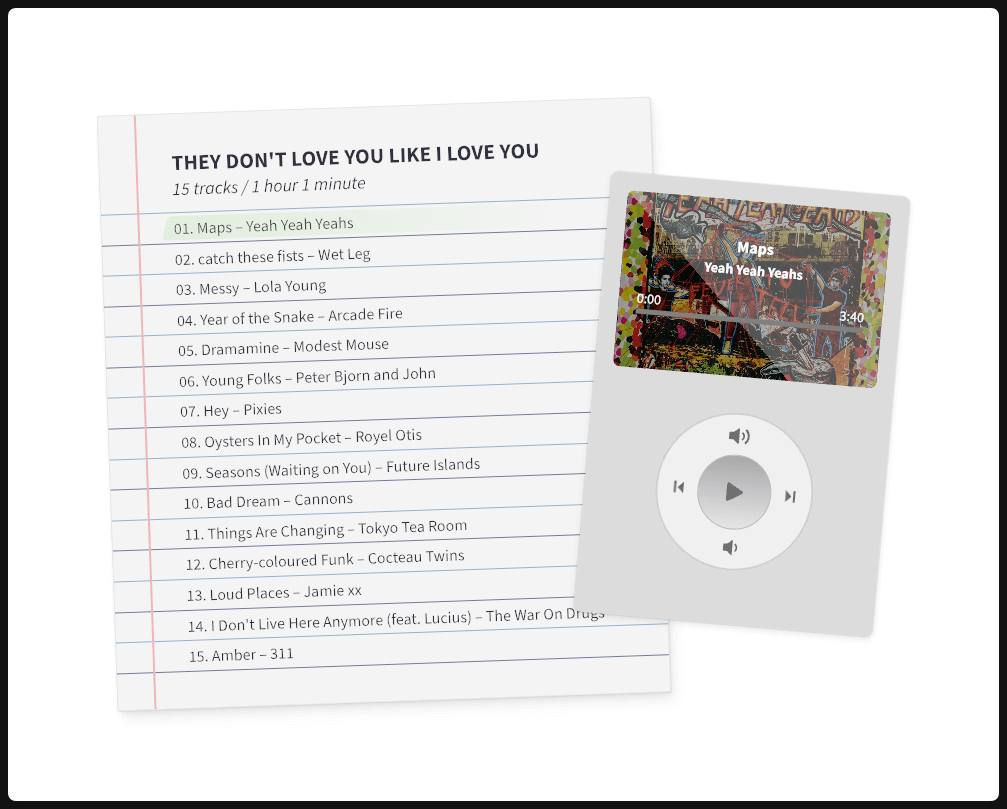

In the latest iteration, I use that same technique to add a playable iPod (and paper playlist), conjuring up as much aughts nostalgia as possible. For the curious, the iPod is on my homepage.

The Basics

Everything is operable, meaning that the volume, previous/next track, and play/pause buttons all do what you expect. There's nothing too revolutionary about that, but I'm a bit of a sucker for skeuomorphic design.

Of course, the iPod shows song progress, relevant album artwork, and the highlighted song on the playlist updates accordingly.

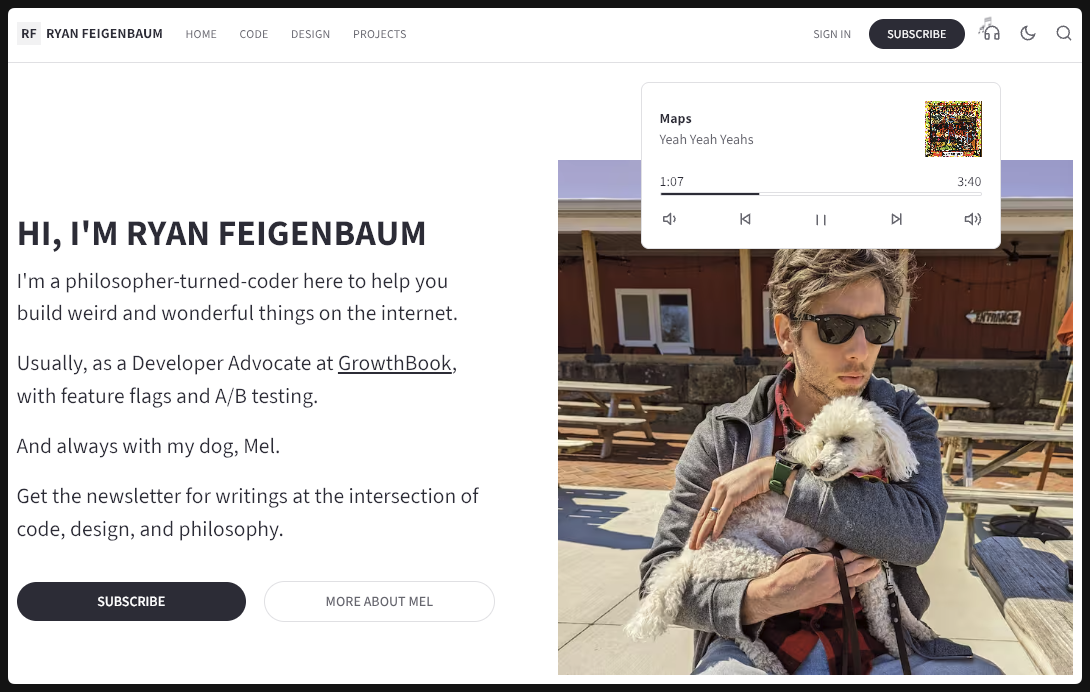

Mini Player, Too

There's also a mini player that lives in the navbar with synced controls. When music's playing, tiny notes float out of the headphone icon à la Arc (RIP).

Because the mini player lives on every page of my site, but the iPod only on the homepage, it was actually more difficult to build than expected, as all the shared methods needed to account for whether both players were present or not.

And how did I build this iPod on my website anyway?

How I Built It: Two Highlights

The central technique, which I detail in the aforementioned post, is embedding a YouTube playlist, hiding it with CSS, and then controlling it programmatically with JS.

An illusion, Michael.

There's lots to talk about here, but I want to focus on two things: lazy loading and how it's built.

Lazy Loaded for Real This Time

In v1 of the music player, I used intersectionObserver to lazy load the code for the music player. That means Google's iframe code was only loaded when the user scrolled the player (nearly) into view. This lazy loading prevented lots of bytes coming down the wire (especially on initial load), but it had a critical flaw.

The music player was loaded no matter what, even if the user had no intention of playing a single, luscious note.

Here's what that looked like:

function callback(entries) {

entries.forEach((entry) => {

if (entry.isIntersecting) {

document.head.append(tag);

window.onYouTubeIframeAPIReady = playlistController;

// eslint-disable-next-line no-use-before-define

observer.unobserve(playlistContainer);

}

});

}

const observer = new IntersectionObserver(callback);

observer.observe(playlistContainer);

How much could this eager loading cost?

Over 900 KBs, 10+ network requests, memory, processing, and more for something that might not even be used.

In v2, I only load the player if the user actually wants to play music. That is, the user has to click/interact with the player first. This kicks off the scripts being loaded, all while showing a loading state.

private bindEvents(): void {

const addEventListeners = (

elements: HTMLButtonElement[],

action: string

) => {

elements.forEach((el) => {

el.addEventListener("click", async () => {

if (!this.player && !this.isLoading) {

// First click initializes YouTube

await this.initializeYouTubePlayer(action);

} else if (!this.isLoading) {

// Subsequent clicks just dispatch events

this.dispatchMusicEvent(action);

}

});

});

};This requires queuing the user's intent (usually "play"), loading the scripts, and then, when ready, executing that action:

private async initializeYouTubePlayer(action: string): Promise<void> {

// If already loading, just queue the action

if (this.isLoading) {

this.queuedAction = action;

return;

}

if (this.player) return;

this.setLoading(true);

this.queuedAction = action; // Store what the user wanted to do

return new Promise<void>((resolve) => {

const tag = document.createElement("script");

tag.src = "https://www.youtube.com/iframe_api";

(window as any).onYouTubeIframeAPIReady = () => {

this.player = new (window as any).YT.Player("player", {

// ... player config ...

events: {

onReady: () => {

this.setLoading(false);

// Execute the queued action!

if (this.queuedAction) {

this.dispatchMusicEvent(this.queuedAction);

this.queuedAction = null;

}

resolve();

},

onStateChange: (e: { data: number }) => this.onPlayerStateChange(e),

},

});

};

document.head.appendChild(tag);

});

}The user clicks play once and music plays. In between, we just queue the action, download and initialize an entire YouTube player, and then programmatically execute the action.

But before we lazy load, we have to build it.

Building New Playlists

What happens when I sweat, toil—or sometimes—haphazardly click my way to a new playlist and want to update my site with the latest and greatest from DJ Rye? (Fun fact: I was a DJ in high school for a hot minute.)

In the first version of this, there was lots of manual futzing to get things updated. This has all been automated now with GitHub Actions (unsung heroes?) and Ghost 〰️ templating.

Here's the full GH Action:

name: Build and deploy theme

on:

workflow_dispatch:

push:

branches:

- main

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-22.04

steps:

- name: Checkout repository

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Setup Node.js

uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: "20"

- name: Install pnpm

run: npm install -g pnpm

- name: Install dependencies

run: pnpm install

- name: Fetch Playlist Data

env:

GOOGLE_API_KEY: ${{ secrets.GOOGLE_API_KEY }}

run: pnpm run fetch-playlist

- name: Fetch readling list Data

env:

RAINDROP_API_KEY: ${{ secrets.RAINDROP_API_KEY }}

run: pnpm run fetch-reading-list

- name: Build theme

run: pnpm run build

- name: Deploy theme

uses: TryGhost/action-deploy-theme@v1

with:

api-url: ${{ secrets.GHOST_ADMIN_API_URL }}

api-key: ${{ secrets.GHOST_ADMIN_API_KEY }}

In my Ghost theme, I have a script directory that has a fetch-playlist script. This action runs that script on build, which fetches my latest playlist from YouTube, formats it, and then outputs the content to a playlist.hbs file in my partials directory.

That playlist.hbs file is a script tag with an application/json type, including the entire playlist as a JSON object.

Here's an example of an entry:

{

"title": "Maps",

"artist": "Yeah Yeah Yeahs",

"songLink": "https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=UKRo86ccTtY",

"url": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/UKRo86ccTtY/default.jpg",

"idx": 0,

"id": "UKRo86ccTtY",

"duration": "3 minutes 40 seconds",

"vidId": "UKRo86ccTtY",

"thumbnail": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/UKRo86ccTtY/maxresdefault.jpg",

"timestamp": "3:40"

}

Then, that data is used to render the actual playlist in the DOM, almost like a mini JS framework. For example, here's how I render a playlist item:

this.playListData.forEach((item, idx) => {

const song = document.createElement("p");

song.dataset.vidId = item.vidId;

song.classList.add("s-playlist-item");

if (idx === 0) song.classList.add("is-active");

song.textContent = `${(idx + 1).toString().padStart(2, "0")}. ${

item.title

} – ${item.artist}`;

playlistContainer.appendChild(song);

});

(BTW. I have whole new way to do code formatting in Ghost—let me know if you want me to do a post on it.)

Any time I rebuild my Ghost theme, it fetches the new playlist data. I can also trigger it manually from GitHub with the workflow_dispatch trigger in the Action file.

This makes it easier to push updated playlists to my site than it is to make playlists, as it should be.

Conclusion

And that's the story of how my site got an iPod and how it runs. Enjoy it while you can, because I'll likely change it dramatically with my new theme (coming soon?!).

Aside from the impractical-but-fun nature of the iPod, it helped me find some fun techniques that just make for good web (and theme) development like strategically loading resource-heavy assets and automating tedious tasks.

My current theme isn't open source right now, but lmk in the comments if you'd like to see the source or share a song I should include on my next mix.

DJ Rye out 🎧