Banksia is a genus of shrub and tree that, with the exception of one species, grows only in Australia.

What first caught my eye about this plant is its flower spike. This inflorescence comprises a woody center surrounded by a cone of small, tightly-packed flowers that number from the hundreds to thousands. One species, Banksia grandis, has even been recorded as having 6,000 flowers in one spike! In some cases, the flowers will fruit in hard and woody cones called follicles, which resemble barnacles attached to the hull of a ship. These fruits release their seeds at varying times or, sometimes, not at all, and some will only release them after they've been burnt in a bushfire. As a result some species are able to withstand fire very well, which explains why the cones can carry a flame a great distance, a property put to frequent use by Aborigines.

Wherever I might walk in Sydney, there's Banksia. Like a mulberry-stained sidewalk that might appear now and then in Philadelphia, the Banksia's woody cones are scattered about the sidewalks in North Bondi, where I live. Here's some photos of the Coastal Banksia trees that line my street.

But this plant hasn't always been called, "Banksia," and, in fact, its christening begins with a journey that wildly trumps the one I griped about in my last post.

- August 1768 - Plymouth Harbor, England

- September - Madeira

- November - Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- January 1769 - Bay of Good Success, Tierra del Fuego

- April - Matavai Bay, Tahiti

- October - Anaura and Tolaga Bay, New Zealand

- April 1770 - Botany Bay, Australia

This is the route that Captain James Cook's HMS Endeavour took to Australia. (I've left out their return to England, but they did make it back, albeit not without a little shipwreck). The idea of the voyage began with the Royal Society's petitioning King George III for an expedition to observe and record the transit of Venus, which would enable a better calculation of the Sun's distance from the Earth, and, in turn, help to establish the size of our solar system more accurately. In addition to this scientific aim, the voyage also had an economic one, to chart and explore the Pacific Ocean and map the coastlines of islands in the South Pacific. These were the stated goals of the Endeavour, but Captain Cook also had (somewhat) secret orders from the British Admiralty, to find a large landmass and take possession of it in the name of the King. In 1770 Cook did just that, first charting eastern Australia and then claiming the continent for Great Britain.

Banksia fits into this story when we consider a yet further purpose of the ship, one not funded by the King but by the wealthy Joseph Banks. (Yes. I'm getting to how the plant is named after this wealthy guy, and was he ever wealthy.) From his estate, Banks received an annual income of £6,000 or today's equivalent of about $1.3 million. In comparison, for the command and navigation of a ship around the entire world, Captain Cook only made £90 ($20,000) per year. Nevertheless, rather than use his finances for a life of indolent luxury, Banks employed himself as the ship's resident naturalist, outfitting it with a slew of the latest instruments for collecting and preserving whatever flora and fauna he may come across as well as hiring a staff of additional naturalists, artists, and servants. It is no surprise, then, that Banks's primary interest in the journey was natural history, and he was thus constantly trawling the sea for various fishes or going ashore in search of rare species. His incessant efforts irritated the crew and Cook, especially given the fact that the Captain had to share his cabin with Banks and whatever species he might be examining at the time.

When Banks was out at sea and couldn't conduct his fieldwork (which was quite often), his daily routine included botanical drawing, electrical experiments, animal dissections, deck-walking, bird-shooting—all of which we know from another one of his daily activities: journal-writing. Banks wrote extensive daily entries detailing the entire voyage. Here's part of an entry from April, 1770, in which Banks records his first glances upon Botany Bay (what is to become Sydney, Australia):

After dinner the Captn proposd to hoist out boats and attempt to land, which gave me no small satisfaction; it was done accordingly but the Pinnace on being lowerd down into the water was found so leaky that it was impracticable to attempt it. Four men were at this time observd walking briskly along the shore, two of which carried on their shoulders a small canoe; they did not however attempt to put her in the water so we soon lost all hopes of their intending to come off to us, a thought with which we once had flatterd ourselves. To see something of them however we resolvd and the Yawl, a boat just capable of carrying the Captn, Dr Solander, myself and 4 rowers was accordingly prepard. They sat on the rocks expecting us but when we came within about a quarter of a mile they ran away hastily into the countrey; they appeard to us as well as we could judge at that distance exceedingly black. Near the place were four small canoes which they left behind. The surf was too great to permit us with a single boat and that so small to attempt to land, so we were obligd to content ourselves with gazing from the boat at the productions of nature which we so much wishd to enjoy a nearer acquaintance with. The trees were not very large and stood seperate from each other without the least underwood; among them we could discern many cabbage trees but nothing else which we could call by any name. In the course of the night many fires were seen.

I must confess I find it dizzying to imagine myself there with Banks in the yawl, looking upon the eastern coast of Australia for the first time, upon a land that none of my fellow country men have yet seen, a land whose very existence at the time was still in doubt and hence had been up to that point mostly unmapped and uncharted. To look upon this terra incognita would, no doubt, be an incomparable experience.

What passes through Banks's mind at that moment, though, reveals the unyielding ambition of the naturalist: he wishes for nothing more than to "gain acquaintance" with nature's productions. Of the many species that Banks would soon pursue and collect in Australia, one plant in particular would end up taking his name in what, I guess, could be considered less of an acquaintance and more of a marriage.

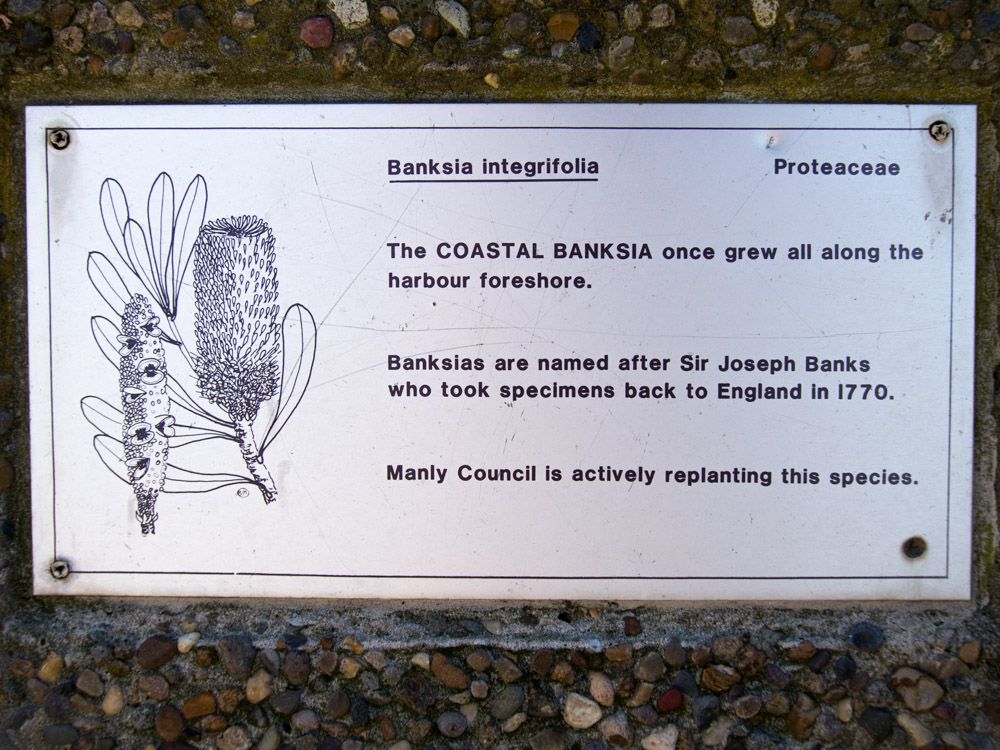

It was after having made landfall in Botany Bay in 1770 that Banks and his companion, Dr. Solander, collected the first four species of the plant whose genus would come to be called Banksia (which included the Banksia integrifolia photographed above). The name became official when the son of Carl Linnaeus, Linnaeus the Younger, published the classification in 1782. From that day on, this plant became Banksia.

The work of its collection and classification continues till the present day with around 173 species currently identified. In 2000, the newest species, Banksia rosserae, was discovered in Western Australia. It is named after Celia Rosser, who has painted every single species of Banksia and collected these illustrations into a three volume book. As much as Banks sought the productions of nature, Rosser sought its artistic reproductions, and both have thus had their names affixed to this plant.

But this name records more than the discovery of a genus and species of plant. For it records as well those moments in which Banks first looks upon what is to become in less than two decades a British colony, and where, more than two centuries later, Rosser will live and I will visit; it records, too, those moments in which Banks sees those four men walking on the shore.

As dizzying as it is to imagine myself beside Banks in the yawl, how much more so to be ashore beside those men, to witness the massive Endeavour sailing into their bay. For these men of the Eora nation the land needed neither charting nor mapping. It was no terra incognita. It was home and had been so for at least the last 40,000 years.

When I first arrived in Sydney I was struck by the flower spikes of this tree that I can't help but recognize now as Banksia, a plant that carries this entire history within its leaves, flowers, and follicles. It connects me to a wealthy landowner from the late 18th century, a man who looked upon the coast of Botany Bay and saw "many fires" in the night, fires that could have burned on the woody cone of a plant that was not yet Banksia, that was another name now lost.