Humans average eight hours of sleep a night, which amounts to you spending one-third of your life asleep. Way to go. You're basically absent from a third of your own life.

You might feel better to know that your absenteeism is nothing compared to the little brown bat. This tiny guy sleeps big: 18-20 hours a night. Relatively, or really, theoretically, humans should be able to get a lot more done than little brown bats, like coming up with words about those missing eight hours of the day. Here, then, are ten must-know, completely trivial words about sleep.

1. Obdormition

(ob-dor-mish-uhn), noun.

Definition: When a limb goes numb due to inactivity or constant pressure.

You're probably on pins and needles to know what this first word means, which, at least in its current sense, only refers to sleep metaphorically. Obdormition is a medical term that describes a phenomenon familiar to anyone who has stayed in one position just a little too long: the going numb of limbs. Whereas you likely would've said, "Shit, my leg fell asleep," you can now say, "Alas, my leg has fallen prey to the obdormition." Beware, though, that saying such things will make you sound like an asshole.

As annoying as obdormition is, the part that follows is far worse. When your leg begins to wake up, it lets you know about it with a general unpleasantness, just like waking up in real life. With life, it's called despair; with the feeling of pins and needles, paresthesia (bonus word!).

2. Soporific

(sop-uh-rif-ik), adjective.

Definition: Inducing sleep or to be sleepy. Dull. Boring.

As hard as waking up may be, sometimes falling asleep isn't any easier. You lie in bed awake, thinking about your dentist appointment tomorrow, wondering where that sound just came from, worrying about something you said in third grade, searching for a solution to climate change, all while ruminating on the cruelty of human finitude.

And you know that sound has to be a roach riding a mouse around like a horse. Or a serial killer.

What you're in need of is a soporific, something to dull the anxieties of modern life and bring on the REM cycles. A glass of warm milk with a side of a roast turkey might do the trick, but Ambien is also a terrific soporific. Just remember the recommended dosage: 1 pill per each desired hour of sleep.

Goodnight, sweet prince!

my body: WHAT DO WE WANT?

— keely flaherty (@keelyflaherty) October 18, 2018

my brain: SLEEP!

my body: WHEN DO WE WANT IT?

my brain: AT EITHER 2PM OR 3AM

my body: hey wait—

my brain: LITERALLY NO OTHER TIME

my body: no that’s not—

my brain: WE ARE UNWILLING TO COMPROMISE

3. Hypnagogic

(hip-nuh-goj-ik), adjective.

Definition: The period right before you conk out or relating to this.

You finished your turkey, had your piping-hot milk. Your eyelids are heavy. Suddenly, though, you're running for your life, chased by a roach riding a mouse dragging a large inflated turkey behind it, like some kind of demented float in a Thanksgiving parade. And to make matters much worse, the roach has a small cowboy hat that he keeps tipping at you. "Hiya, Partner!"

This is an example of a hypnagogic hallucination, or a vision that occurs right before sleep. August Kekulé's discovery of the chemical structure of benzene provides a famous example, as the molecule's peculiar structure revealed itself to him in a bout of hypnagogia. He described the hallucination as follows:

I turned my chair to the fire and dozed. [...] But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes.

Kekulé had a vision of a snake biting its own tail, or an ouroboros (bonus word!), that unveiled the ring-like structure of benzene. If you're now hoping that your hypnagogic state will unveil some mystery of the natural world, don't hold your breath. It's much more likely to be a vision of a demented holiday-parade float or an alien abduction, the latter of which some experts attribute to hypnagogic states.

4. Myoclonus

(mahy-ock-luh-nuh s), noun.

Definition: Crazy-ass, random twitching of muscles. Sometimes a symptom of a neurological disorder.

You're just about to fall asleep, and then, BAM, you're falling off a forkin' mountain, and your body tweaks out like you're Catherine O'Hara in that dinner scene from Beetlejuice.

That's a myoclonic jerk, a common form of myoclonus, which is a medical term that signifies a sudden, involuntary muscle twitch. Hiccups are another example. Myoclonus etymologically stems from "myo," a prefix formed from the Greek μῦς (mus) or muscle, and the Ancient Greek κλόνος or "clonus," which means agitation.

Sidebar: From the beginning (even in the Ancient Greek), the word for "muscle" comes from the word for mouse or hamster. The etymology of the English word "muscle," for instance, means "little mouse," ostensibly because some muscles, like the bicep, resemble the furry creature. So, instead of asking passersby whether they have tickets to the gun show as you tenderly kiss your flexed biceps, just ask them whether they have tickets to the hamster show. It will truly be a weird flex, but (etymologically) OK.

In summary, your brain does this really cool thing when you're right about to fall asleep: it makes you think you're plummeting to your death and shocks your leg like a fish slapping around the bottom of a boat.

But, why, brain?!

To be honest, no one knows. One evolutionary musing holds that it's the body misinterpreting muscle relaxation to be a dozing ape falling from a tree. The myoclonic jerk is a reminder to reposition yourself in the branch. Others think it's the last gasp of the awake, raging against the dying of the light. Or, some say, it's just the brain being random, like, "OK, time to fall asleep. JK. You're falling off a forkin' mountain. LOL."

5. Doss

(dos), noun.

Definition: Sleep or a makeshift place to sleep.

You've made it midway through the list, from falling asleep to doss, an informal, totally outmoded, primarily British word for sleep. Its etymological origin is unclear, but experts suspect the word stems from the Latin word for back (dossum), which gives us words like dorsal and dossier. The latter is so-called, apparently, because the bundle of papers bore a label on its spine.

Doss also means a place for sleep where you don't usually sleep and where you wouldn't particularly want to. It relates to "dosshouse," which is British for "flophouse," which is grandma for "shithole." You might've dossed down in a questionable hostel or two when you were studying abroad in college. Or, when you completely ran out of money, you might've dossed down in the Valencia bus station, only to be rudely awoken by a police officer smacking you with his baton, yelling, "Get up," in Spanish. No doss that night.

NB: In Scotland, doss seems to have become a favorite adjective to pair with cunt, like pinot noir with duck. In this case, the word means "stupid" or "thick," and, for whatever reason, it doesn't seem nearly as offensive if you imagine it being said with a Scottish accent, as in "Fuck aff ye doss cunt, aam tryin' tae sleep."

6. Subeth

(suh-beth), noun.

Definition: The deepest of deep sleeps.

No longer in the dosshouse, you have found yourself at home, sweet, home. Sheets of an astronomical thread count, fresh and cool to the touch, crisply cover the mattress. Your pillow gently cradles your head as a final warm summer breeze blows in over the crisp autumn night. You are free from hypnagogic hallucinations and myoclonic jerks. Nothing disturbs you as as you slip into the most restful sleep of your life, or subeth.

The word "subeth" comes from the Latin subet, borrowed from the Arabic subāt, which is cognate with the Hebrew word that gives us "Sabbath." Subeth is incredibly rare, finding virtually no usage in the past 300 years. Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster don't even have a listing for it.

The rarity of this word and its declining usage is fittingly emblematic of just how hard it is to get a good night's sleep these days.

7. Hypnopedia

(hip-nuh-pee-dee-uh), noun.

Definition: Sleep isn't just for snoring, it's also for learning.

You probably find, like many, that sleep is your least productive part of the day. Well, that's because you're doing it wrong.

Why just sleep, when you could be sleep-learning, or practicing hypnopedia? Like similar words on this list, the first part of "hypnopedia" is formed from the Ancient Greek word for sleep, hypnos. The latter half comes from the word for education, paideia.

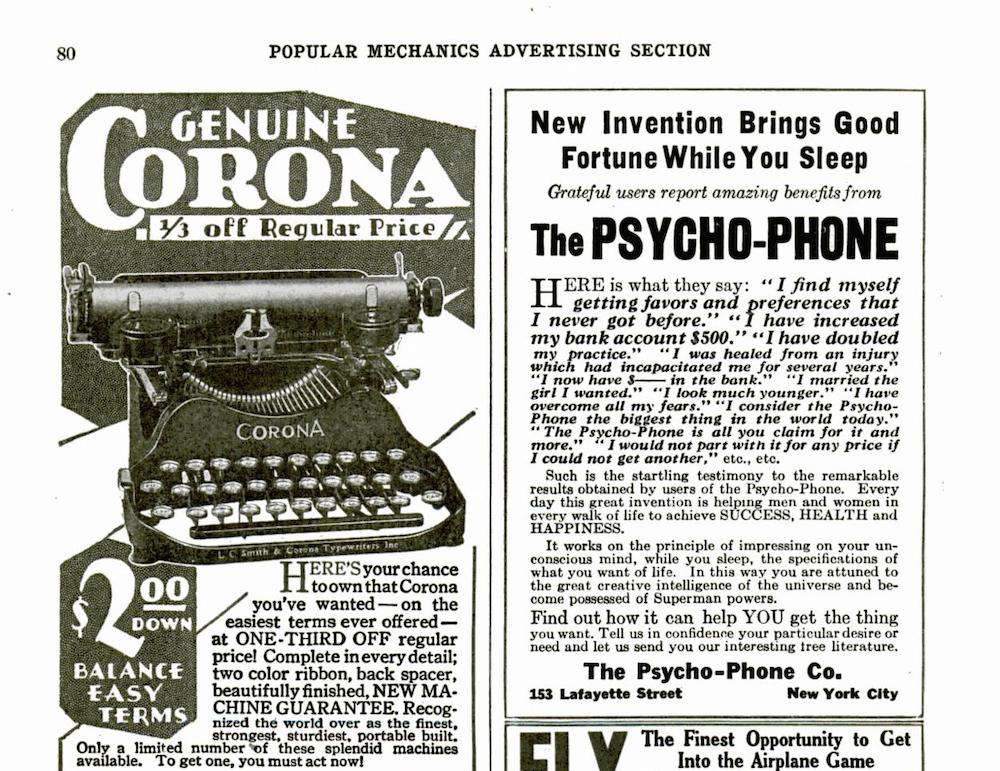

Now largely debunked, hypnopedia was scientifically investigated in the early to mid-20th century as a real possibility. Interest in the phenomenon seems to have begun with the publication of Hugo Gernsback's serialized science fiction story, Ralph 124C 41+ (1911). In addition to containing sometimes prescient reference to other later-realized inventions, Gernsback described the hypnobioscope, a device that transmitted information to a sleeper via a headset. In Brave New World (1932), Aldous Huxley also mentioned hypnopedia, as a way to morally condition children. These literary references became a reality when the entrepreneur Alois Benjamin Saliger developed and sold the psycho-phone. This device, an Edison phonograph that played motivational tapes while the owner slept, was purported to bring its user "good fortune." Basically, it was The Secret of the 1920s.

In the 1950s and '60s, hypnopedia reached a fever pitch. Numerous experiments were being conducted around the world–always with inconclusive or dubious results. An article published in a Soviet psychology journal cited Huxley's novel, along with the works of other fiction authors, as conclusive evidence of hypnopedia's success. Even the US Department of Defense got in on the fun by using hypnopedia to teach personnel Morse code.

Other experiments, however, confirmed the opposite: hypnopedia was nothing more than pseudoscience. Using electroencephalography (by which a machine records the brain's electrical activity), Charles W. Simon and William H. Emmons demonstrated it was likely impossible to learn anything while asleep.

Or is it? Research in 2012 suggests that while learning new information isn't possible, hypnopedia may be able to reinforce existing knowledge.

In conclusion, before scampering off to the Land of Nod, put your old biology textbook under your pillow. Yes, this is how it works. When you wake up a biology genius, you're welcome.

8. Oneiric

(oh-nigh-rick), adjective.

Definition: Of or relating to dreams. Dreamlike.

Dreams are the stuff of weird shit happening. You pull a sailboat from your pocket. Your head becomes a seasonal gourd. It rains croissants, snows donuts, and sleets cronuts. You save Ariana Grande's life. You wake up (in your dream) happy about it.

The outlandish quality of these occurrences makes them dreamlike or oneiric, which comes from the Ancient Greek word (ὄνειρος or oneiros) for dream. Interestingly, though oneiric means dreamlike, it's not synonymous with dreamy. For instance, Idris Alba, dreamy for sure, but Rami Malek? A little dreamy, mostly oneiric. You can't help but worry that his eyeballs are going to pop out of their sockets like Popeye squeezes spinach from a can.

my mom said she likes rami malek bc he reminds her of our dog and i cannot unsee this pic.twitter.com/0aOgGtRWwj

— b (@6rineh) February 27, 2019

To be able to call something oneiric presumes you have some experience of dreams, but it doesn't require you to know what they are or what function they play in human life. Don't feel bad, though. No one does. Dreams remain a pending question for science and religion, now and all through recorded history.

One aspect of this history is oneirocritica (bonus word!) or the interpretation of dreams. Oneirocritica, in fact, is the title of the first extant work of dream interpretation in Greek. Artemidorus authored the text in the 2nd century CE. The premise for the work is that dreams, correctly interpreted, can predict your future. There's a long section on sex dreams, and a special section on dreams where you sleep with your mom (oh hi, Oedipus). There are sections on dreams that recur and on animals that appear in your dream. Did you say you saw a partridge in your dream?

Not good.

Artemidorus writes that partridges could represent a man or woman, but generally they represent godless, unholy women who ain't good to their man. (Oneirocritica is not a feminist text.) As everyone knows, Artemidorus says, partridges are hard to tame, mottled, and they're the only kind of bird that has no respect for the gods. Absolutely none. He goes on, if you see a partridge in your dream, you better check your boo's phone, because she's probably sliding into someone else's DM's. Or whatever people say now.

9. Somnambulism

(som-nam-buh-liz-uhm), noun.

Definition: A cooler sounding word for sleepwalking.

All your waking life you've probably been led to believe that sleep is concomitant with a lack of productivity, and were consequently shocked when you learned about hypnopedia above. What if you could wake up tomorrow already having walked 120,000 steps (roughly, 56.82 miles), all while asleep? Add in some language lessons playing through your headphones, and you're waking up a polylingual power-walker by the end of the week.

The foolproof method for getting those steps in is somnambulism or sleepwalking. The word comes from the Latin somnus, meaning sleep, and ambulare, meaning to walk.

Sidebar: Ambulare is also the etymological root of the word "ambulance." Does that mean the etymology of ambulance, an emergency vehicle, comes from the word to walk, like, you just got pulled from burning wreckage and the ambulance is just gonna saunter you over to the hospital, but maybe stop for a smoothie if there's a place on the way?

There must be another explanation. Maybe the etymology of ambulance is due to the fact that it's the thing that gets you up and walking again, like, hate to break it to you, buddy, but if the ambulance doesn't deliver you from that heap of flames, say goodbye to walking.

Unfortunately (or fortunately), the actual etymology is far more mundane and far less stupid. "Ambulance" derives from the French "ambulance," which was originally hôpital ambulant, that is, a walking or mobile hospital. Before the word took on its modern meaning of an emergency vehicle, hôpital ambulant referred to mobile hospitals erected near the edge of battle sites to treat wounded soldiers. In the Crimean War (1853–56), "ambulance" came to refer to the vehicle itself that transferred the wounded to these hospitals. Note that this history only refers to the emergence of the word "ambulance," not to the existence of a vehicle used to transport the sick, which has been around for a long, long time.

Somnambulating 50 miles in the dead of night is a recipe for disaster, no doubt. As you awaken to find yourself in an ambulance, take comfort in knowing you're living in an age where trained EMTs frantically work on you, machines wildly beep around you, and other medical supplies festoon the vehicle walls, for these are all quite recent innovations. Until about the mid-20th century, ambulances were only meant for transport, not healing. It was the patient's responsibility to hang on long enough to reach the hospital. If you didn't make it, you could take refuge in the fact (at least in the US before 1970) that you weren't still being such a burden in death, because hearses were ambulances, ambulances were hearses, and the Ghostbuster's Ecto-1 is an iconic example.

10. Hypnopompic

(hip-nuh-pom-pik), adjective.

Definition: The period right before waking up or relating to this.

Whereas hypnagogic refers to the period immediately before sleep, hypnopompic refers to the period right before sleep's departure. Hypnopompic derives from the Ancient Greek words for sleep and sending away (πομπή or pompē).

The hallucinations common to hypnagogic states extend to hypnopompic ones, too. F. E. Leaning, who produced a massive 130-page study of hypnagogia in 1925, describes both states as "a certain degree of drowsiness, a twilight condition of consciousness in which pseudo-hallcuinations, which are neither waking visions nor dreams, can occur" (289).

Leaning goes on to recount the hypnopompic vision of a young man, who, upon waking, sees a cowboy hunched over in his closet. The young man rises from his bed to see what has so intensely caught the cowboy's attention.

The young man finds the cowboy training a roach to doff his cowboy hat, and, though it is almost imperceptibly faint, the drowsy young man swears that the roach is yelling, "Mornin', Partner," as it rides a mouse into the rising dawn.